David Armstrong’s Poignant Photographs Offer Insight Into a Bygone Era

An important exhibition pays tribute to the late artist, one of the most influential—and, until now, under-recognized—photographers of his generation.

If David Armstrong hadn’t been a photographer, he would have made a brilliant writer. He was a keen lover of words, wisecracks, and stories, and to this day, a decade after his death, friends still quote his pithy observations or the stray bits of droll dialogue he repurposed from turn-of-the-century novels or 1950s films. In his genteel, matronly singsong voice, he’d be as apt to deliver a fragment from Edith Wharton or a verse from the Bible as he would a personal saga from the late 1980s involving a friend in the East Village who’d jumped from his fire escape. Looking back at his five decades of work, you can sense an almost literary penchant for character and atmosphere. In his deceptively straightforward portraits, he captured not only the complicated personas of his sitters but also their entire social milieus.

Armstrong grew up in Arlington, Massachusetts, six miles northwest of Boston. He was one of four siblings; his father was in construction, and his mother worked for an insurance agency. In the late ’70s, he attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, in Boston, alongside the rising like-minded photographers Mark Morrisroe, a punk visualist and performance artist who died in 1989 of AIDS, and Nan Goldin, whose powerful documentation of the private lives of an entire subculture and her recent anti-opioid activism have made her one of the most important living American artists. (Armstrong was the one who originally shortened her name from Nancy.) Curiously, while Armstrong often seemed like a creature from a previous century, he was very much at the center of a radical, bohemian group that couldn’t have been more attuned to the moment. “David was like someone out of a novel,” recalls the artist Jack Pierson, who met Armstrong in 1981 in Boston, when Pierson was attending the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Pierson, Armstrong, Morrisroe, and Goldin would eventually be known as the “Boston school” for their unnervingly direct photography styles that captured the beauty, sexual charge, and countercultural mess of their everyday lives. Nonetheless, for many, Armstrong remains one of the most under-recognized photographers of the late 20th century.

Hairstylist Mary Cruz and a friend, 1979.

A young Nan Goldin in Provincetown, Massachusetts, late 1970s.

Curator Klaus Biesenbach in Berlin, early 1990s.

That could soon change. This June, at the Kunsthalle Zürich, one of the most prestigious contemporary art spaces in Switzerland, an extensive collection of Armstrong’s early portraits will be on view in the first major show of his work since he died of cancer, in 2014. The exhibition is cocurated by the New York artist Wade Guyton, a friend of Armstrong’s, and the Kunsthalle’s director, Daniel Baumann. In addition to showcasing 100 of the artist’s own vintage prints, the retrospective will include several vitrines of contact sheets that highlight how Armstrong approached his portrait shoots and how he ultimately selected the final images. Part of the reason Baumann felt drawn to Armstrong’s artistry—particularly his work from the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s—is the potent sense of vulnerability encoded in the material. “We don’t have that anymore,” the curator says about our current relationship to the still image. “Having your picture taken has been totally changed by social media. We are living in a post-authentic world—today people stage intimacy as a form of self-promotion or special standing.”

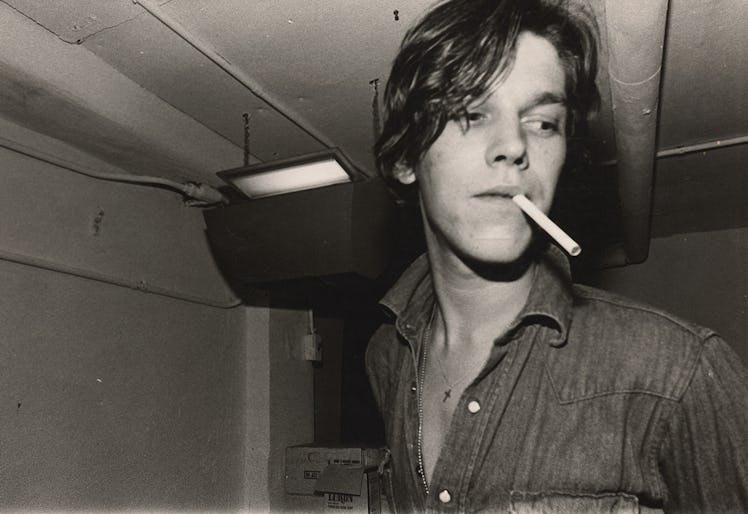

Early on in college, Armstrong developed the habit of photographing his friends, creating emotive compositions so mesmerizing that they could only have been drawn from shared experiences. “In the summer of ’81,” Pierson recalls, “I rented an apartment in Provincetown with Mark Morrisroe and Stephen Tashjian [the artist Tabboo!]. David came out and stayed with a friend of his who was a clammer and friends with the whole John Waters crowd. The fact that David not only knew people like John Waters and Cookie Mueller but also had taken photos of them was a huge deal to us. We were clutching our copies of Shock Value [Waters’s 1981 memoir] to tell us how to live and become famous.” Armstrong shot his merry band of misfits smoking, swimming, and sunbathing, their lithe bodies on full display. He was known for his wizardlike ability to capture natural light, and in his portraits a gorgeous, atmospheric radiance gives the impression of a moment lasting much longer than the time it takes to press a button. These would become some of his most enduring images—the denizens of the underground beautifully libidinal en plein air.

Actor Bruce Balboni, scenic artist George Kousoulides, Max Mueller (son of actor Cookie Mueller), and a friend in Provincetown, late 1970s.

John and Evan Lurie, of the band the Lounge Lizards, in New York City, 1980.

Hairstylist Jimmy Paul in New York City, 1991.

Provincetown offered the decidedly urbane, cramped-apartment-dwelling characters in Armstrong’s orbit the backdrop of a classic seaside idyll, but neither he nor his gang could resist the pull of New York City. In the mid-1980s, Armstrong photographed East Village friends, lovers, painters, actors, writers, musicians, and strangers who caught his eye. Several of these young artists would go on to have legendary careers—Jean-Michel Basquiat, Vincent Gallo, John Lurie, Teri Toye, Rene Ricard, and Christopher Wool among them. The names of others have been lost to time, but in these pictures the sitters—whether they are famous or not, people Armstrong had known his entire adult life or simply had a brief crush on—usually pose in a casual, unaffected manner, sitting on an unmade bed, leaning against a wall, or resting on a pillow. The bond that Armstrong felt with them leaves a strong emotional imprint. We, too, can fall in love with his friends.

Armstrong’s portraits are not reportage, and they don’t have Nan Goldin’s feeling of raw, caught-off-guard ephemerality. His subjects are clearly posing, but there is always a sense that their authentic selves are coming through, as full human beings with complicated contradictions, aware of the then unusual experience of having their photo taken. “David’s photographs show a certain melancholy in the way people look into the camera,” Baumann notes. “Melancholia is a mood of the 20th century that I don’t see so much these days. There’s also a degree of boredom that has disappeared—imagine it’s a Wednesday afternoon and having no clue as to what to do and finding someone in the streets who is also utterly bored to hang out with.” There is little urgency or hurry in Armstrong’s photographs. These are not young New Yorkers late for work or rushing on their lunch hour. And even though Armstrong’s subjects tend to have a strong personal style, there is no self-promotion, no proto-influencer trying to advertise a lifestyle. The only message is: Be young, alive, and free.

Actor Sophie Vdt in New York City, 1979.

Artist Jack Pierson in his New York City studio, 1991.

Jay Johnson, once a Warhol Factory regular, in New York City, late 1970s.

Balboni with underground icons (from left) Linda Olgeirson, Sharon Niesp, and Cookie Mueller at Herring Cove Beach, Provincetown, 1975.

Armstrong continued to make work up until his death. In the new millennium, he expanded his practice, shooting fashion campaigns and editorials, as well as a portrait series on New York hustlers, and developing his ongoing suite of blurred landscape photographs that have the classical beauty of European painting. For much of this time, he sequestered himself in a rambling, curio-filled brownstone in Brooklyn. In his last years, he moved up to the Berkshires, in Western Massachusetts, to convalesce as the witty maiden aunt he seemed destined to become. By then, a younger generation of artists and photographers had found inspiration in his bohemian spirit and idiosyncratic photography, adopting him as a spiritual or aesthetic guide. The photographer Ethan James Green began assisting Armstrong in 2011, after meeting him on a shoot a few years prior, when Green was modeling. The relationship quickly developed into a close mentorship. “I’m not really sure where I would be without David,” says Green. “He taught me about light and the importance of integrity, but his influence extended beyond photography. He showed me who I could be as a person and mirrored an acceptance that allowed me to embrace my full self. He changed my life.”

There was an ineffable, magical quality to Armstrong, a generosity of spirit that spilled over into everything he did and left a mark on everyone he touched. He remained, to the end, wise and kind and open-hearted, but no less shrewd and discerning. He hated phonies. Pierson recalls the many times he spotted Armstrong in New York City, running around with a box of prints under his arm. “David,” he says softly, “always had the aura of a star.”

Poet and artist Rene Ricard at home in New York City, 1979.

Magazine editor Lisa Love in Provincetown, mid-1970s.

Cookie Mueller in New York City, 1978.

Artist Christopher Wool in New York City, 1980.